| Patrick Morley

Tells Stories |

MORE RANDOM

THOUGHTS

ON THE CENTRAL SCHOOL

Those I

remember

The boys I

remember: Freddie Buxton, Sid Lakin, Don Ackforth, Fatty

Robinson, Bonny Mason, Dave Milner, Blondie Laker, Bob (?) Trickett,

George Birley, Haigh, Foxon, Wood, Wilkinson. (See

list of 1940 intake)

And those who tried to teach us: Miss Hepworth, Miss Collis, Polly Wood, Katy

Street, Mr Poole, Mr Morris, Avro Hanson, Mr Cooke, Froggy Levy, Pongo

Molyneux, Treth Trethowan, Haj Elsey, Squeak Weston, Mr Hainsworth, and Mr

Swaine.

Why “Polly”

and why “Pongo”, I wonder. And what happened to them afterwards? Some figure

on school photos from a later era but I’d love to see a picture - in

particular of Miss Hepworth, my favourite.

And let’s

not forget the two school secretaries whose names I don’t recall and also

Ernie Sharrett who I recall worked for a time as laboratory assistant at

Abbey Street. He and I had gone to Wilmorton Junior School together. Someone

told me he’d come to a sad end but I have no details.

I can remember

only one occasion when the school reacted to the war news. One summer morning we arrived at the old school building in Abbey Street, where

we went once a week for chemistry lessons, only to be sent home again. It was

Tuesday June 6, D-Day. We'd heard about the Normandy landings on the news

at breakfast time. But first reports just seemed to suggest it was nothing

more than a big raid, like those on St Nazaire and Dieppe. But it soon

emerged that this was the moment we -- and all occupied Europe -- had been

waiting for. We were back in France, almost four years exactly since the

Germans had seen us off in such humiliating fashion.

In the

town, people in the queues were all talking about the news. A special

edition of the Derby Evening Telegraph was rushed on to the streets, a rare

event in those days. The headlines were huge (they only used big type then

if it was something really important):

|

The

War

At

school, I was doing well at French. We all read a lot about the French

Revolution and the exploits of the Scarlet Pimpernel. So it was satisfying

to be able to understand the French expressions which peppered the stories.

But the war was an even bigger encouragement to learn the language. Like

General de Gaulle's famous message to his people after the Fall of France,

calling "A tous les Francais" to join him in the fight against Hitler. You'd

have thought Miss Wood, our French teacher, would have got us to translate

it as part of our lessons. After all, it was real - to do with the war going

on around us. But no, we had to plough on with the usual dreary passages out

of our exercise books. So I struggled through it myself with the aid of a

dictionary and felt quite pleased when I'd rendered it into English. Had I

got it right? I asked Miss Wood, hoping for a word of praise. All I got was a

dismissive sniff and the suggestion I would be better concentrating on the

lessons I had been set.

She was not alone

in her attitude. Here we were involved in a world war, the greatest war in

history, but for all the notice that was taken of it it might not have

existed. The only time we ever talked about it with the staff was if we

raised it ourselves. For instance, we asked Mr. Weston (Squeak) what he

thought when Hitler invaded Russia. All he said was: Remember Napoleon and

the Russian Winter. He proved to be right as it happened but he clearly

thought (with some truth) that we were trying to distract him from the

serious business of learning. We were at school to pass the School

Certificate and everything else was irrelevant. We boys talked a great deal

about the war among ourselves but would have welcomed what would now be

considered Current Affairs sessions with teachers who obviously were better

informed than we were. But it wasn’t a School Cert subject so it didn’t

count. Disappointing and surprising.

I can remember

only one occasion when the school reacted to the war news. One summer morning we arrived at the old school building in Abbey Street, where

we went once a week for chemistry lessons, only to be sent home again. It was

Tuesday June 6, D-Day. We'd heard about the Normandy landings on the news

at breakfast time. But first reports just seemed to suggest it was nothing

more than a big raid, like those on St Nazaire and Dieppe. But it soon

emerged that this was the moment we -- and all occupied Europe -- had been

waiting for. We were back in France, almost four years exactly since the

Germans had seen us off in such humiliating fashion.

In the

town, people in the queues were all talking about the news. A special

edition of the Derby Evening Telegraph was rushed on to the streets, a rare

event in those days. The headlines were huge (they only used big type then

if it was something really important):

It was a thrilling moment. For so

long life had been dull with nothing much to look forward to. Now you could

feel how excited everyone was. At last we'd show Hitler what was what. Maybe

the war really would be over by Christmas. What a wonderful thought!

“Dropping”

|

In the autumn of 1942 I

entered the Third Form and marked the occasion by 'dropping’ - going from

short to long trousers. It was always a special occasion. When you 'dropped’

didn't depend entirely on age. It also mattered how big you were and whether

you felt the moment was right. The war added another factor: clothes

rationing.Not only were they rationed in quantity. So was the choice of

material, no matter how much money you'd got. The Government brought in

Utility clothing.

There were only a few types of

cloth and the price was controlled. So we all had to make do. |

|

People carried on

wearing clothes they would once have sent to a jumble sale. It didn't matter

so much if you went around looking a bit shabby. Darns and patches became

respectable. One of our masters, Mr. Poole, was a tall, elegant man who

always wore what were clearly expensive suits. But even he came to school

with leather elbow patches.

Obviously, a new pair of

trousers for me would use up many precious clothing points. So I did the

same as most of my schoolfellows - raided my brothers' wardrobe. They were

away in the Army so weren't going to be needing the contents for some while.

I commandeered the trousers from a smart, grey-striped suit. They fitted

passably well, were expensive and looked it. But they weren't quite right

separated from the jacket that should have gone with them. That wouldn't fit

me at all. The trousers had turn-ups which you didn't get with Utility in

order to save material. So my mother let them down and in ironing out the

creases slightly singed the cloth. My debut in long trousers was not

therefore the sartorial triumph I had hoped for. But it was a landmark.

By now, like the rest of

Form Four, I was beginning to be preoccupied with sex. We discussed its

precise nature endlessly but facts were hard to come by.

There were no sex lessons and

no text books. So we seized on any scrap of knowledge we could find. Every

reference to sex in the books we read, every anatomical diagram in medical

text books added to our hazy understanding, or confused us all the more. We

were so ignorant we had no idea that the daring pictures of nude girls in

magazines like Lilliput and Men Only, which we studied with close interest,

had been doctored to hide the indelicacy of pubic hair. Most of us had no

idea there was such a thing. Sometimes we tried to buy copies of the nudist

magazine Health and Efficiency but usually the shopkeeper refused to sell

them to us.

Most of what we knew about sex

came to us in only one way. We all now began reciting lewd verses and

telling each other dirty jokes. That was what sex seemed to be about:

something secret, 'rude,' to be sniggered at.

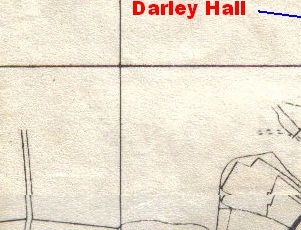

We went on hunts for French

letters, as condoms were called. In summer, the slopes of Darley Park were

covered with the prostrate figures of servicemen (Americans usually) and

their girls. The litter of 'Frenchies' in the grass was proof of what they'd

been doing. We deduced all these activities must have something to do with

the mysterious advertisements that began to appear in the newspapers about

VD.

We weren't in the least bit

clear what venereal disease was or how you got it, but it was clearly

something to be avoided. The fact that the notices were also to be seen in

public lavatories gave us the impression that you might catch it from

sitting on the seat after someone else had used it. So we wasted reams of

precious paper cleaning lavatory seats and needlessly sitting on layers of

protective 'bum fodder.'

|

On the buses it became an art

to pace yourself when you followed a girl to the top deck to be just the

right distance behind at the steepest part of the stairs. Then you could

look up and see right up her skirt. You rarely got a glimpse of stocking

tops. Silk stockings had practically vanished and nylons, just introduced

from America, were a great rarity. To give the appearance of stockings girls

used leg make-up, a brown dye they painted on with varying results.

Sometimes it was so bright it looked revolting but applied with just the

right touch it could be as enticing as the real thing, even more so if a

non-existent seam was painted on as well.

A lot of knicker spotting went

on at school. The women teachers often perched themselves on a desk and as

soon as they did, pens or pencils clattered to the floor. We'd bend down to

pick them up and from the low-angle vantage point shoot a swift glance up

the teacher's skirt. Stocking tops were a rare treat, the sight of knickers

a greater one. |

For just one term we had a

young and pretty French girl to teach us the language -- I think she was a

refugee who somehow had got out of occupied France. Her name was Miss

Doudal, or that’s what it sounded like. When she had set us an exercise she

used to perch herself on one of the big window seats so she could watch us

but it wasn’t easy for us to see her. It became a point of honour as to who

could get a glimpse up her skirt. I tried the pencil dropping routine but

young though she was she knew at once what I was up to. You are a very rude

boy she snapped and ordered me out of the class for the rest of the lesson.

Trying to look up women’s

skirts was as near to sex as most of us got. But it didn't stop us dreaming

about it. One evening I was at an ARP dance at the local school hall. With

me was Robbo, one of my school pals, helping me to put on the gramophone

records. A girl of about 18, the sister of another school friend, had had

too much to drink. She confided to us that one of the records, Glen Miller's

"In The Mood" made her feel "all queer." Only moments before Robbo told me

that he found it so sexy that it could give him an erection. "It gives me a

funny feeling, too," he said at once to the girl and asked her for a dance.

She was so taken aback that even though there were plenty of servicemen

there she agreed. Robbo couldn't really dance but he managed to get round

the floor a few times. I could see he was pressing himself against her.

When he came back I knew from

his expression that the music had had the same affect again. "You're a

little devil," the girl said. She was a tarty looking female with too much

makeup. I asked her quickly if I could have a dance, too. She looked at me

for a moment. "You're too young," she said and moved off in search of more

promising material.

Her words wounded me. I was

actually older than Robbo and a couple of inches taller. But then, I

consoled myself, she wasn't the sort of girl my mother would have approved

of. I decided I'd better wait until a nice girl came along. The trouble was

nice girls didn't let you press yourself against them. Robbo knew what I was

thinking. He laughed. "You haven't got the knack," he said.

We put "In the Mood" on again

and watched the girl jitterbugging with an airman. Her skirt flew up as she

twisted round the floor and we saw she was wearing mauve knickers. I sighed.

"Never mind," Robbo said. "Wait till you're in uniform. Then you'll get the

girls." It was a comfort of sorts.

Getting There

There were no such things then as school buses: you

used the same buses as everyone else. And with so few cars because of petrol

rationing, the buses were packed out. Sometimes six or seven would sail past

full. In the winter, when not so many people cycled to work, you could stand

waiting in the freezing cold for half an hour or more. It was no joke

especially if you’d been up half the night in the air raid shelter because

the sirens had gone.

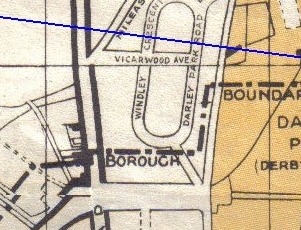

I lived at Alvaston so I had to change buses in

the Market Place. From there the trolley went up Irongate, past the Queen

Street baths where we had our swimming sessions, and on past Derby School

(evacuated during the war to Amber Valley). At the Five Lamps the bus

took the right fork to the trolley terminus at the junction of Duffield Road

and Broadway. Then a long walk to the school, first an unmade lane to the

park gates with the school allotments on the right then down the path

through the park that brought us at last to the school.

Going home - if it was a nice summer’s day - we walked all the way through the

park and out of the back entrance past some rows of tall early Victorian

houses coming out at last in Bridge Gate. On one side was the elegant Roman

Catholic church of St. Mary’s with the tall spire of St Alkmund’s on the

other.

|

I always got real pleasure walking through St Alkmund’s

Churchyard which was one of the few bits of old Derby still surviving.

I wasn’t surprised to read as an adult that Nicholas Pevsner in his Buildings of

England described it as "unmatched, a quiet oasis of 18th century Derby."

The city planners evidently didn’t rate Pevsner's views very highly. When I

visited Derby 50 years later I found St Alkmund’s and the quiet oasis had

gone completely. In its place was the frenetic Inner Ring Road, an

unsightly scar which had ripped apart much of what was left of the Derby I

remembered. |

St. Alkmund's Churchyard in the 1950s |

Caning [I dealt with caning at some length in my BYGONE DERBY article which

is already on the website. Here are a few additional thoughts]

Apart from

Squeak Weston the other really fierce caner was “Treth” (Mr Trethewey.) He

was normally a pleasant well liked teacher but when he wielded the cane

(which was infrequent) look out! I remember examining the weals he had

inflicted on a fellow pupil’s hands -- deep purple wounds (there is really

no other word). The boy’s hands were shaking uncontrollably and there was no

way he could possibly use a pen. I couldn’t understand why we were caned on

the hand. Apart from making it difficult to write if you got a really hard

caning there was always the danger of breaking or damaging a boy’s finger.

Much better surely to have you bend over. It would hurt but wasn’t likely to

cause any serious damage and it didn’t stop you writing your essays which

caning on the hand often did. Women (apart from the sadistic young mistress

I have already mentioned) rarely used the cane. Miss Wood never, Miss

Hepworth hardly ever. As far as “Polly” Wood was concerned her viciously

sharp tongue was feared far more than a caning, which is perhaps why she

never needed to use it.

Change

at the Top

In 1944 we found

ourselves with a new headmaster. I suppose there must have been some

announcement and perhaps a farewell presentation to Mr Hainsworth who had

been the head since well before the war. I certainly don’t remember

anything of the sort. We were sorry to see Mr Hainsworth go. You certainly

wouldn’t have called him a colourful figure but he was a man we all

respected. He was not someone to take liberties with. He maintained

discipline but he was essentially fair. I don’t think I ever saw him smile

but he never raised his voice either that I recall.

What would the new

head be like, we wondered. Mr Swaine came from a very different mould to his

predecessor. Looking back, I should think he was a warm hearted,

understanding man who would enjoy a joke. Certainly I can’t imagine Mr

Hainsworth reacting as he did to my escapade with the paint brush (see

article below entitled March 25). Nor can I imagine him caning a whole line

of boys himself for skating on the ice. But all that is with the benefit of

hindsight. I think at first we older boys thought he seemed more

approachable than we had been accustomed to. Mr Hainsworth had been stern

looking and kept properly aloof. But his successor’s style of management,

as we would say today, was quite different and it would take some getting

used to. Schoolboys tend to be conservative and prefer what is familiar. So

we treated GB, as we came to call him, with some caution. Let him prove

himself and we would come to have the same regard for him as for his

predecessor. Time would tell.

Pongo Molyneaux

Mr Cook

was our English master. He was clearly devoted to the subject but oddly

enough we didn’t get as much reaction out of him as we did from “Pongo”

Molyneaux who took English from time to time. He was a large, balding man

with a booming voice and he was given to expressing himself forcibly. One day

we were reading aloud from Hereward the Wake. After enduring Kingsley’s

turgid, convoluted prose for ten minutes or so Pongo suddenly flung his copy

down in exasperation. “This wretched book needs abridging in large chunks”

he announced. How we agreed with him.

| He had

firm views about the English language.

In an indulgent moment, he

allowed us to write an essay on our favourite film star. In my eulogy of

Errol Flynn I used the phrase ‘swashbuckling hero.’ "Where ever did you

get that word," he boomed." Disgusting Americanism. No such word exists

in the English language."

I found it later in the school

copy of the two volume Oxford English Dictionary. I was about to show it

to him triumphantly but decided on reflection it might be wiser to keep

quiet. |

Errol Flynn as swashbuckling Captain Blood. |

But there

were times when he was prepared to listen to what you had to say. On

another occasion we were set to write a piece about a recent film we had

enjoyed. Two or three of us chose an Abbott and Costello mystery comedy “Who

Done It.” Pongo wasn’t having of that. “Totally ungrammatical. Not

acceptable,” he thundered. And he insisted we entitle the essay “Who Did

It.” But, we pointed out, that was not the title of the film,

ungrammatical though that undoubtedly was. Finally we agreed on a

compromise. “Who Done It [sic] More Properly Who Did It.” I can’t imagine

any other teacher who would have been prepared even to discuss the matter.

On Tuesday

each week we went to Abbey Street for chemistry lessons. It had a remarkably

roomy and well equipped laboratory and the lecture theatre with its rows

of climbing benches was impressive. But compared with Darley Park mansion it

was a dreary place and every time I went there I gave thanks that the one

good thing about the war was that it had put us in such a lovely setting.

Apart from which as far as I was concerned chemistry was a dead loss. My

solutions never crystallised, my experiments rarely came out right. I

couldn't remember the formula for anything except water and concentrated

sulphuric acid -- and that only because it was what had deformed the

villain in "Phantom of the Opera" (Claude Rains and Susanna Foster).

|

"Being but humble sergeants and corporals ..."

in front of AFN mike. |

Abbey

Street did have one advantage. Just round the corner was a fish and chip

shop which served chips that were a real delight. More than that the

wireless was always on and it was tuned into a programme which I

discovered was AFN, the American Forces

Network, set up specially for

the US troops flooding into Britain for the invasion of Europe. What a

revelation that was. Before long most of us at school were listening to AFN.

If you didn't tune in regularly to AFN you just weren't in the picture.

It

was a revelation: the jokey, friendly announcers - such a contrast to the

stiffness of the BBC. From AFN we got the best of the American comedy shows:

Bob Hope, Jack Benny, Burns and Allen, Charlie McCarthy. We learned

something of the mysteries of baseball and American football; we

listened with interest to shows like the American equivalent of the

Brains |

|

The unforgettable Burns and Allen comedy duo |

Trust, called Information

Please. But most

of all it was the music we wanted to hear. We listened to as much pop as any

teenager nowadays though it wasn't called pop. We tuned in to request

programmes like Duffle Bag, were devoted to Corporal Johnny Kerr and other

turntable maestros. We listened to them with as much informed attention as

any modern DJ's radio show.

We knew what was top of The Hit Parade and the morning after they'd been

played on AFN we were arguing about whether this

number or that should have been higher on the list. We discussed the

relative merits of the big bands, Benny Goodman or Tommy Dorsey. We imagined

ourselves drumming like Gene Krupa. We swooned over Dinah Shore and we

fought over Crosby and Sinatra. March

1945

At school, I'd been made a prefect but my term of office was very nearly

a brief one, all because of a famous wartime murder trial. |

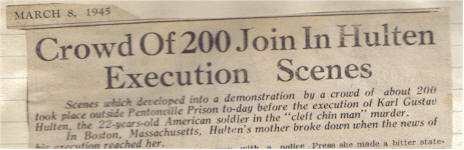

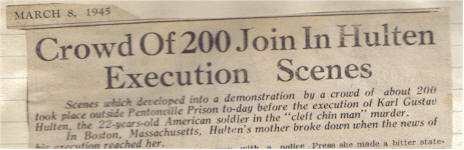

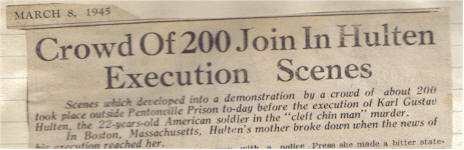

This was the Cleft Chin murder

case involving what the newspapers called "a gunman and his moll." The

gunman, whose named was Hulten, was an American soldier, a deserter posing

as an officer. The moll was an 18 year old English girl called Jones, a

dancer in a night club. They staged a series of violent robberies and

finally killed a taxi driver, a man with a cleft chin. The Americans handed

Hulten over to British justice and the two were found guilty and sentenced

to death.

|

An original press cutting of the Hulten case. Left, the strip-tease

dancer Elizabeth Jones. Their victim was a certain Edward Heath!! |

On the eve

of the execution, the girl was reprieved by the Home Secretary, Mr Morrison.

But he decided the soldier must hang. At school, we were outraged at this

injustice. Clearly, either both should hang or neither. From the evidence,

the girl Jones had seemed as vicious as her partner, Hulten, and had egged

him on to commit more crimes "for the excitement of it."

We decided

our views should be made known and I was chosen to make a grand gesture on

behalf of all of us. I found a tin of white paint and daubed a suitably

restrained slogan on the school wall:

HANG JONES HANG MORRISON SET HULTEN FREE

We agreed

that should do the trick. It did. In assembly, the Head announced grimly

that when he found the boy responsible he'd give him the hiding of his life.

It was a disconcerting moment. Discovery seemed probable and as a prefect I

carried a certain responsibility. Perhaps I should have thought of that

earlier.

I decided

to confess. The Head (G.B. Swaine, known simply as G.B.) was always

lecturing us on courage and honesty. Given his anger, it took a certain

amount of both to own up. I hoped I might get the credit for that. It was a

calculated risk but one I felt worth taking. In the event, it paid off.

Instead of the expected outburst once I had owned up to my misdeed, the Head

stood looking out of the window. Then what he said was not what I expected

to hear. "Do you know any girls the same age as this girl Jones," he asked.

"Can you imagine any of them getting involved with a gunman as she did?" And

he went on to talk at length about how easy it is to be tempted, especially

in wartime, for a young girl from a poor home whose head had been turned by

dreams of glamour and money. The French girls who had succumbed to the lure

of German soldiers came to my mind.

At the end

of it all, he didn't strike me off the list of prefects or even cane me. I

had to clean the paint off the wall of course. But I'd expected that. The

whole episode gave me much food for thought. It set my fellow prefects

thinking as well. Perhaps there was more to G.B. than met the eye....

Being a

prefect had certain privileges. In the depths of winter you didn’t have to

stand outside in the freezing cold waiting to be let in. You sauntered

grandly through the door and warmed yourself at the fire blazing in the main

hall. You also more or less had the run of the building. In the winter you

could go down into the basement and keep warm by the main boiler. In

summertime you could always find an excuse to admire the sweeping views

across the park from the roof, normally strictly out of bounds. One day a

group of us including Dave Milner decided to explore the roof space. Dave

lost his footing on one of the beams and stepped on the ceiling. The next

moment his foot went straight through. We grabbed him, hauled him back on to

the beam and beat a hasty retreat. But as ill luck would have it the room

below was where Squeak Weston was presiding over the boys who had taken

packed lunches. Suddenly there was crash and part of the ceiling actually

fell on him. A few moments later we met him on the landing coming down from

the roof. “Ah prefects,” he shouted. “Some wretched boy has been in the roof.

Quick! Get up there and see if you can catch him.” I’m sure we did our best

but somehow the “wretched boy” eluded us…..

Elections, Mock and

Real

In the

summer of 1945 I went on the first seaside holiday we’d been able to have

since the war began and all the beaches were closed to the public “for the

duration.” I was on the Isle of Wight when we heard who had won the General

Election that had been held soon after we had beaten the Germans. We'd had a

mock election at school. I was the Conservative candidate and my election

programme came straight out of the Daily Express which announced confidently

that Labour's chances were remote. I won at school by a handsome majority.

Reality was different. In the Labour landslide victory, Derby returned two

Labour M.P.s Some while later I received a school prize from one of them,

Group Capt Wilcock who seemed a pleasant cheerful sort of man. The prize he

handed over amused my mother no end: The Life and Times of Winston Churchill

Spring 1946

Cricket

we played in Darley Park but football wasn't allowed there for fear of

churning up the turf. So we used Darley Playing Fields, on the other side of

the river. This involved a trek through Darley Abbey, crossing the Derwent

by the mill and on down to the playing fields. On a wet cold afternoon it

wasn’t much fun especially as I didn’t excel at sport. All the same

I did go to all of Derby

County’s home games and was also keen on horse racing. At school, this was

looked on not as a sport but a vice. One day I'd marked the card for a

particularly tricky Newmarket meeting when a teacher spotted me with the

SPORTING CHRONICLE. From the way he reacted you'd think I had a copy of one

of Dr. Goebbels' Nazi propaganda newspapers. I got a long lecture on the

wickedness of trying to get something for nothing and then had to watch in

helpless dismay as my list of selections was screwed up and flung into the

wastepaper basket along with the rest of the paper.

What he

would have said had he ever known about my escapade over the school wireless

set and the 1,000 Guineas I shudder to think. I had put the princely sum of

half a crown each way on the King's horse Hypericum and I was desperate to

listen to the race. The only wireless in the school was in the dining hall

and normally there was no safe way of getting at it during the day. But as

luck would have it, on the afternoon of the race we were taking part in a

sports day at the far end of Darley Park, so the entire school was gathered

there. I concocted some excuse to return to the school building and slipping

into the deserted dining room, turned on the wireless. I had timed it

perfectly. The race was about to begin: a couple of minutes and I could

return safely to the sports with no one the wiser. Then to my horror,

Hypericum bolted.

She was

eventually caught and the race began a quarter of an hour late. All the time

I was in dread of someone suddenly appearing and finding me in the act. But

my fears soon vanished in the excitement of the race. In spite of having run

the length of the course once, Hypericum won easily -- and I was the

richer by getting on for three pounds. That would have been worth being

caned for. But when I returned to the sports no-one seemed to have noticed

how long I'd been away.

Bullying

It seems

to be commonplace at schools today but I was certainly never bullied and I

can’t recall a single instance of real or systematic bullying (as distinct

from calling people names or giving them a shove now and then) in the six

years I was at the Central School.

AFTERTHOUGHT

A quarter

of a century after leaving school I met a young woman who had also been to

school in Derby though some years later than me. It turned out she had gone

to Parkfield Cedars, whose girls we had lusted after vainly long ago. Which

school did you go to, she asked. Derby School or Bemrose? When I told her

Central School she turned her nose up. Oh that wasn’t a proper grammar

school she said. I was hurt and annoyed. What a nerve! Not a proper grammar

school indeed. Just what you’d expect from one of those toffee nosed girls

at Parkfield Cedars…..

Comments on

other contributions

Email: October 2nd, 2005

What a pleasure it was to

read

John Garratt's piece on school dinners.

A delightful piece of atmospheric writing. John and I were colleagues many

years ago on the Evening Telegraph. How strange therefore I didn't realise

he and I had both been at the Central School -- or perhaps I did and had

forgotten.

I stopped having school dinners after consuming a

cheese pie that made me violently sick. As a result I didn't eat cheese for

many years afterwards. I did resume school dinners after a while. I think my

mother got fed up of giving me "packing up" especially when food became

harder and harder to get.

I also read

Peter Eyre's piece with interest. He

and I must have worked together on the Telegraph which I joined in 1946 but

I cannot for the life of me place him. As he rightly says memory plays

strange tricks. He is right of course about there being a school special

trolley bus from the Market Place to Darley Park. Because it looked like any

other Corporation bus it became fixed in my mind as a service bus. In fact I

think we often had to catch a service bus especially if we had been waiting

in the cold and rain during winter to catch the bus from Alvaston into town

after the special had gone. Now I come to think about it there was also a

special school bus from the Darley Park terminus down the Broadway

to...where? Can't remember!

Two other points from

Peter's email: I never meant to suggest the 1940 intake list was complete

because I'm sure it wasn't. And re. Don Acford: sorry if I spelled his name

wrongly but I was never sure if it was Ackforth or Ackford. One further

point: I certainly never meant to suggest that no one bothered about the

war. Very much the contrary: it was with us all the time. The point I was

making was that as far as I was concerned (and my experience was obviously

different from Peter’s) the teaching staff rarely mentioned it and certainly

didn’t bring it (as they could easily have done) into any of our lessons,

especially French and Geography as well as History.

Peter’s article also reminds

me that the “tarty teacher” I mentioned in one of my articles must have been

the Miss Ferguson he refers to. And that reminds me of another woman teacher

who was only with us for perhaps a year if that -- Miss Collis. She was a

very pleasant easy going lady, quite young, who had the misfortune to have a

rather unsightly wart on her face.

More later but meanwhile all the best. Patrick (Morley)

Other of Patrick's

memories were published in the DET Bygones section [Home] Page updated:

Saturday, 04 August 2007 |

It was a thrilling moment. For so

long life had been dull with nothing much to look forward to. Now you could

feel how excited everyone was. At last we'd show Hitler what was what. Maybe

the war really would be over by Christmas. What a wonderful thought!

“Dropping”

|

In the autumn of 1942 I

entered the Third Form and marked the occasion by 'dropping’ - going from

short to long trousers. It was always a special occasion. When you 'dropped’

didn't depend entirely on age. It also mattered how big you were and whether

you felt the moment was right. The war added another factor: clothes

rationing.Not only were they rationed in quantity. So was the choice of

material, no matter how much money you'd got. The Government brought in

Utility clothing.

There were only a few types of

cloth and the price was controlled. So we all had to make do. |

|

People carried on

wearing clothes they would once have sent to a jumble sale. It didn't matter

so much if you went around looking a bit shabby. Darns and patches became

respectable. One of our masters, Mr. Poole, was a tall, elegant man who

always wore what were clearly expensive suits. But even he came to school

with leather elbow patches.

Obviously, a new pair of

trousers for me would use up many precious clothing points. So I did the

same as most of my schoolfellows - raided my brothers' wardrobe. They were

away in the Army so weren't going to be needing the contents for some while.

I commandeered the trousers from a smart, grey-striped suit. They fitted

passably well, were expensive and looked it. But they weren't quite right

separated from the jacket that should have gone with them. That wouldn't fit

me at all. The trousers had turn-ups which you didn't get with Utility in

order to save material. So my mother let them down and in ironing out the

creases slightly singed the cloth. My debut in long trousers was not

therefore the sartorial triumph I had hoped for. But it was a landmark.

By now, like the rest of

Form Four, I was beginning to be preoccupied with sex. We discussed its

precise nature endlessly but facts were hard to come by.

There were no sex lessons and

no text books. So we seized on any scrap of knowledge we could find. Every

reference to sex in the books we read, every anatomical diagram in medical

text books added to our hazy understanding, or confused us all the more. We

were so ignorant we had no idea that the daring pictures of nude girls in

magazines like Lilliput and Men Only, which we studied with close interest,

had been doctored to hide the indelicacy of pubic hair. Most of us had no

idea there was such a thing. Sometimes we tried to buy copies of the nudist

magazine Health and Efficiency but usually the shopkeeper refused to sell

them to us.

Most of what we knew about sex

came to us in only one way. We all now began reciting lewd verses and

telling each other dirty jokes. That was what sex seemed to be about:

something secret, 'rude,' to be sniggered at.

We went on hunts for French

letters, as condoms were called. In summer, the slopes of Darley Park were

covered with the prostrate figures of servicemen (Americans usually) and

their girls. The litter of 'Frenchies' in the grass was proof of what they'd

been doing. We deduced all these activities must have something to do with

the mysterious advertisements that began to appear in the newspapers about

VD.

We weren't in the least bit

clear what venereal disease was or how you got it, but it was clearly

something to be avoided. The fact that the notices were also to be seen in

public lavatories gave us the impression that you might catch it from

sitting on the seat after someone else had used it. So we wasted reams of

precious paper cleaning lavatory seats and needlessly sitting on layers of

protective 'bum fodder.'

|

On the buses it became an art

to pace yourself when you followed a girl to the top deck to be just the

right distance behind at the steepest part of the stairs. Then you could

look up and see right up her skirt. You rarely got a glimpse of stocking

tops. Silk stockings had practically vanished and nylons, just introduced

from America, were a great rarity. To give the appearance of stockings girls

used leg make-up, a brown dye they painted on with varying results.

Sometimes it was so bright it looked revolting but applied with just the

right touch it could be as enticing as the real thing, even more so if a

non-existent seam was painted on as well.

A lot of knicker spotting went

on at school. The women teachers often perched themselves on a desk and as

soon as they did, pens or pencils clattered to the floor. We'd bend down to

pick them up and from the low-angle vantage point shoot a swift glance up

the teacher's skirt. Stocking tops were a rare treat, the sight of knickers

a greater one. |

For just one term we had a

young and pretty French girl to teach us the language -- I think she was a

refugee who somehow had got out of occupied France. Her name was Miss

Doudal, or that’s what it sounded like. When she had set us an exercise she

used to perch herself on one of the big window seats so she could watch us

but it wasn’t easy for us to see her. It became a point of honour as to who

could get a glimpse up her skirt. I tried the pencil dropping routine but

young though she was she knew at once what I was up to. You are a very rude

boy she snapped and ordered me out of the class for the rest of the lesson.

Trying to look up women’s

skirts was as near to sex as most of us got. But it didn't stop us dreaming

about it. One evening I was at an ARP dance at the local school hall. With

me was Robbo, one of my school pals, helping me to put on the gramophone

records. A girl of about 18, the sister of another school friend, had had

too much to drink. She confided to us that one of the records, Glen Miller's

"In The Mood" made her feel "all queer." Only moments before Robbo told me

that he found it so sexy that it could give him an erection. "It gives me a

funny feeling, too," he said at once to the girl and asked her for a dance.

She was so taken aback that even though there were plenty of servicemen

there she agreed. Robbo couldn't really dance but he managed to get round

the floor a few times. I could see he was pressing himself against her.

When he came back I knew from

his expression that the music had had the same affect again. "You're a

little devil," the girl said. She was a tarty looking female with too much

makeup. I asked her quickly if I could have a dance, too. She looked at me

for a moment. "You're too young," she said and moved off in search of more

promising material.

Her words wounded me. I was

actually older than Robbo and a couple of inches taller. But then, I

consoled myself, she wasn't the sort of girl my mother would have approved

of. I decided I'd better wait until a nice girl came along. The trouble was

nice girls didn't let you press yourself against them. Robbo knew what I was

thinking. He laughed. "You haven't got the knack," he said.

We put "In the Mood" on again

and watched the girl jitterbugging with an airman. Her skirt flew up as she

twisted round the floor and we saw she was wearing mauve knickers. I sighed.

"Never mind," Robbo said. "Wait till you're in uniform. Then you'll get the

girls." It was a comfort of sorts.

Getting There

There were no such things then as school buses: you

used the same buses as everyone else. And with so few cars because of petrol

rationing, the buses were packed out. Sometimes six or seven would sail past

full. In the winter, when not so many people cycled to work, you could stand

waiting in the freezing cold for half an hour or more. It was no joke

especially if you’d been up half the night in the air raid shelter because

the sirens had gone.

I lived at Alvaston so I had to change buses in

the Market Place. From there the trolley went up Irongate, past the Queen

Street baths where we had our swimming sessions, and on past Derby School

(evacuated during the war to Amber Valley). At the Five Lamps the bus

took the right fork to the trolley terminus at the junction of Duffield Road

and Broadway. Then a long walk to the school, first an unmade lane to the

park gates with the school allotments on the right then down the path

through the park that brought us at last to the school.

Going home - if it was a nice summer’s day - we walked all the way through the

park and out of the back entrance past some rows of tall early Victorian

houses coming out at last in Bridge Gate. On one side was the elegant Roman

Catholic church of St. Mary’s with the tall spire of St Alkmund’s on the

other.

|

I always got real pleasure walking through St Alkmund’s

Churchyard which was one of the few bits of old Derby still surviving.

I wasn’t surprised to read as an adult that Nicholas Pevsner in his Buildings of

England described it as "unmatched, a quiet oasis of 18th century Derby."

The city planners evidently didn’t rate Pevsner's views very highly. When I

visited Derby 50 years later I found St Alkmund’s and the quiet oasis had

gone completely. In its place was the frenetic Inner Ring Road, an

unsightly scar which had ripped apart much of what was left of the Derby I

remembered. |

St. Alkmund's Churchyard in the 1950s |

Caning [I dealt with caning at some length in my BYGONE DERBY article which

is already on the website. Here are a few additional thoughts]

Apart from

Squeak Weston the other really fierce caner was “Treth” (Mr Trethewey.) He

was normally a pleasant well liked teacher but when he wielded the cane

(which was infrequent) look out! I remember examining the weals he had

inflicted on a fellow pupil’s hands -- deep purple wounds (there is really

no other word). The boy’s hands were shaking uncontrollably and there was no

way he could possibly use a pen. I couldn’t understand why we were caned on

the hand. Apart from making it difficult to write if you got a really hard

caning there was always the danger of breaking or damaging a boy’s finger.

Much better surely to have you bend over. It would hurt but wasn’t likely to

cause any serious damage and it didn’t stop you writing your essays which

caning on the hand often did. Women (apart from the sadistic young mistress

I have already mentioned) rarely used the cane. Miss Wood never, Miss

Hepworth hardly ever. As far as “Polly” Wood was concerned her viciously

sharp tongue was feared far more than a caning, which is perhaps why she

never needed to use it.

Change

at the Top

In 1944 we found

ourselves with a new headmaster. I suppose there must have been some

announcement and perhaps a farewell presentation to Mr Hainsworth who had

been the head since well before the war. I certainly don’t remember

anything of the sort. We were sorry to see Mr Hainsworth go. You certainly

wouldn’t have called him a colourful figure but he was a man we all

respected. He was not someone to take liberties with. He maintained

discipline but he was essentially fair. I don’t think I ever saw him smile

but he never raised his voice either that I recall.

What would the new

head be like, we wondered. Mr Swaine came from a very different mould to his

predecessor. Looking back, I should think he was a warm hearted,

understanding man who would enjoy a joke. Certainly I can’t imagine Mr

Hainsworth reacting as he did to my escapade with the paint brush (see

article below entitled March 25). Nor can I imagine him caning a whole line

of boys himself for skating on the ice. But all that is with the benefit of

hindsight. I think at first we older boys thought he seemed more

approachable than we had been accustomed to. Mr Hainsworth had been stern

looking and kept properly aloof. But his successor’s style of management,

as we would say today, was quite different and it would take some getting

used to. Schoolboys tend to be conservative and prefer what is familiar. So

we treated GB, as we came to call him, with some caution. Let him prove

himself and we would come to have the same regard for him as for his

predecessor. Time would tell.

Pongo Molyneaux

Mr Cook

was our English master. He was clearly devoted to the subject but oddly

enough we didn’t get as much reaction out of him as we did from “Pongo”

Molyneaux who took English from time to time. He was a large, balding man

with a booming voice and he was given to expressing himself forcibly. One day

we were reading aloud from Hereward the Wake. After enduring Kingsley’s

turgid, convoluted prose for ten minutes or so Pongo suddenly flung his copy

down in exasperation. “This wretched book needs abridging in large chunks”

he announced. How we agreed with him.

| He had

firm views about the English language.

In an indulgent moment, he

allowed us to write an essay on our favourite film star. In my eulogy of

Errol Flynn I used the phrase ‘swashbuckling hero.’ "Where ever did you

get that word," he boomed." Disgusting Americanism. No such word exists

in the English language."

I found it later in the school

copy of the two volume Oxford English Dictionary. I was about to show it

to him triumphantly but decided on reflection it might be wiser to keep

quiet. |

Errol Flynn as swashbuckling Captain Blood. |

But there

were times when he was prepared to listen to what you had to say. On

another occasion we were set to write a piece about a recent film we had

enjoyed. Two or three of us chose an Abbott and Costello mystery comedy “Who

Done It.” Pongo wasn’t having of that. “Totally ungrammatical. Not

acceptable,” he thundered. And he insisted we entitle the essay “Who Did

It.” But, we pointed out, that was not the title of the film,

ungrammatical though that undoubtedly was. Finally we agreed on a

compromise. “Who Done It [sic] More Properly Who Did It.” I can’t imagine

any other teacher who would have been prepared even to discuss the matter.

On Tuesday

each week we went to Abbey Street for chemistry lessons. It had a remarkably

roomy and well equipped laboratory and the lecture theatre with its rows

of climbing benches was impressive. But compared with Darley Park mansion it

was a dreary place and every time I went there I gave thanks that the one

good thing about the war was that it had put us in such a lovely setting.

Apart from which as far as I was concerned chemistry was a dead loss. My

solutions never crystallised, my experiments rarely came out right. I

couldn't remember the formula for anything except water and concentrated

sulphuric acid -- and that only because it was what had deformed the

villain in "Phantom of the Opera" (Claude Rains and Susanna Foster).

|

"Being but humble sergeants and corporals ..."

in front of AFN mike. |

Abbey

Street did have one advantage. Just round the corner was a fish and chip

shop which served chips that were a real delight. More than that the

wireless was always on and it was tuned into a programme which I

discovered was AFN, the American Forces

Network, set up specially for

the US troops flooding into Britain for the invasion of Europe. What a

revelation that was. Before long most of us at school were listening to AFN.

If you didn't tune in regularly to AFN you just weren't in the picture.

It

was a revelation: the jokey, friendly announcers - such a contrast to the

stiffness of the BBC. From AFN we got the best of the American comedy shows:

Bob Hope, Jack Benny, Burns and Allen, Charlie McCarthy. We learned

something of the mysteries of baseball and American football; we

listened with interest to shows like the American equivalent of the

Brains |

|

The unforgettable Burns and Allen comedy duo |

Trust, called Information

Please. But most

of all it was the music we wanted to hear. We listened to as much pop as any

teenager nowadays though it wasn't called pop. We tuned in to request

programmes like Duffle Bag, were devoted to Corporal Johnny Kerr and other

turntable maestros. We listened to them with as much informed attention as

any modern DJ's radio show.

We knew what was top of The Hit Parade and the morning after they'd been

played on AFN we were arguing about whether this

number or that should have been higher on the list. We discussed the

relative merits of the big bands, Benny Goodman or Tommy Dorsey. We imagined

ourselves drumming like Gene Krupa. We swooned over Dinah Shore and we

fought over Crosby and Sinatra. March

1945

At school, I'd been made a prefect but my term of office was very nearly

a brief one, all because of a famous wartime murder trial. |

This was the Cleft Chin murder

case involving what the newspapers called "a gunman and his moll." The

gunman, whose named was Hulten, was an American soldier, a deserter posing

as an officer. The moll was an 18 year old English girl called Jones, a

dancer in a night club. They staged a series of violent robberies and

finally killed a taxi driver, a man with a cleft chin. The Americans handed

Hulten over to British justice and the two were found guilty and sentenced

to death.

|

An original press cutting of the Hulten case. Left, the strip-tease

dancer Elizabeth Jones. Their victim was a certain Edward Heath!! |

On the eve

of the execution, the girl was reprieved by the Home Secretary, Mr Morrison.

But he decided the soldier must hang. At school, we were outraged at this

injustice. Clearly, either both should hang or neither. From the evidence,

the girl Jones had seemed as vicious as her partner, Hulten, and had egged

him on to commit more crimes "for the excitement of it."

We decided

our views should be made known and I was chosen to make a grand gesture on

behalf of all of us. I found a tin of white paint and daubed a suitably

restrained slogan on the school wall:

HANG JONES HANG MORRISON SET HULTEN FREE

We agreed

that should do the trick. It did. In assembly, the Head announced grimly

that when he found the boy responsible he'd give him the hiding of his life.

It was a disconcerting moment. Discovery seemed probable and as a prefect I

carried a certain responsibility. Perhaps I should have thought of that

earlier.

I decided

to confess. The Head (G.B. Swaine, known simply as G.B.) was always

lecturing us on courage and honesty. Given his anger, it took a certain

amount of both to own up. I hoped I might get the credit for that. It was a

calculated risk but one I felt worth taking. In the event, it paid off.

Instead of the expected outburst once I had owned up to my misdeed, the Head

stood looking out of the window. Then what he said was not what I expected

to hear. "Do you know any girls the same age as this girl Jones," he asked.

"Can you imagine any of them getting involved with a gunman as she did?" And

he went on to talk at length about how easy it is to be tempted, especially

in wartime, for a young girl from a poor home whose head had been turned by

dreams of glamour and money. The French girls who had succumbed to the lure

of German soldiers came to my mind.

At the end

of it all, he didn't strike me off the list of prefects or even cane me. I

had to clean the paint off the wall of course. But I'd expected that. The

whole episode gave me much food for thought. It set my fellow prefects

thinking as well. Perhaps there was more to G.B. than met the eye....

Being a

prefect had certain privileges. In the depths of winter you didn’t have to

stand outside in the freezing cold waiting to be let in. You sauntered

grandly through the door and warmed yourself at the fire blazing in the main

hall. You also more or less had the run of the building. In the winter you

could go down into the basement and keep warm by the main boiler. In

summertime you could always find an excuse to admire the sweeping views

across the park from the roof, normally strictly out of bounds. One day a

group of us including Dave Milner decided to explore the roof space. Dave

lost his footing on one of the beams and stepped on the ceiling. The next

moment his foot went straight through. We grabbed him, hauled him back on to

the beam and beat a hasty retreat. But as ill luck would have it the room

below was where Squeak Weston was presiding over the boys who had taken

packed lunches. Suddenly there was crash and part of the ceiling actually

fell on him. A few moments later we met him on the landing coming down from

the roof. “Ah prefects,” he shouted. “Some wretched boy has been in the roof.

Quick! Get up there and see if you can catch him.” I’m sure we did our best

but somehow the “wretched boy” eluded us…..

Elections, Mock and

Real

In the

summer of 1945 I went on the first seaside holiday we’d been able to have

since the war began and all the beaches were closed to the public “for the

duration.” I was on the Isle of Wight when we heard who had won the General

Election that had been held soon after we had beaten the Germans. We'd had a

mock election at school. I was the Conservative candidate and my election

programme came straight out of the Daily Express which announced confidently

that Labour's chances were remote. I won at school by a handsome majority.

Reality was different. In the Labour landslide victory, Derby returned two

Labour M.P.s Some while later I received a school prize from one of them,

Group Capt Wilcock who seemed a pleasant cheerful sort of man. The prize he

handed over amused my mother no end: The Life and Times of Winston Churchill

Spring 1946

Cricket

we played in Darley Park but football wasn't allowed there for fear of

churning up the turf. So we used Darley Playing Fields, on the other side of

the river. This involved a trek through Darley Abbey, crossing the Derwent

by the mill and on down to the playing fields. On a wet cold afternoon it

wasn’t much fun especially as I didn’t excel at sport. All the same

I did go to all of Derby

County’s home games and was also keen on horse racing. At school, this was

looked on not as a sport but a vice. One day I'd marked the card for a

particularly tricky Newmarket meeting when a teacher spotted me with the

SPORTING CHRONICLE. From the way he reacted you'd think I had a copy of one

of Dr. Goebbels' Nazi propaganda newspapers. I got a long lecture on the

wickedness of trying to get something for nothing and then had to watch in

helpless dismay as my list of selections was screwed up and flung into the

wastepaper basket along with the rest of the paper.

What he

would have said had he ever known about my escapade over the school wireless

set and the 1,000 Guineas I shudder to think. I had put the princely sum of

half a crown each way on the King's horse Hypericum and I was desperate to

listen to the race. The only wireless in the school was in the dining hall

and normally there was no safe way of getting at it during the day. But as

luck would have it, on the afternoon of the race we were taking part in a

sports day at the far end of Darley Park, so the entire school was gathered

there. I concocted some excuse to return to the school building and slipping

into the deserted dining room, turned on the wireless. I had timed it

perfectly. The race was about to begin: a couple of minutes and I could

return safely to the sports with no one the wiser. Then to my horror,

Hypericum bolted.

She was

eventually caught and the race began a quarter of an hour late. All the time

I was in dread of someone suddenly appearing and finding me in the act. But

my fears soon vanished in the excitement of the race. In spite of having run

the length of the course once, Hypericum won easily -- and I was the

richer by getting on for three pounds. That would have been worth being

caned for. But when I returned to the sports no-one seemed to have noticed

how long I'd been away.

Bullying

It seems

to be commonplace at schools today but I was certainly never bullied and I

can’t recall a single instance of real or systematic bullying (as distinct

from calling people names or giving them a shove now and then) in the six

years I was at the Central School.

AFTERTHOUGHT

A quarter

of a century after leaving school I met a young woman who had also been to

school in Derby though some years later than me. It turned out she had gone

to Parkfield Cedars, whose girls we had lusted after vainly long ago. Which

school did you go to, she asked. Derby School or Bemrose? When I told her

Central School she turned her nose up. Oh that wasn’t a proper grammar

school she said. I was hurt and annoyed. What a nerve! Not a proper grammar

school indeed. Just what you’d expect from one of those toffee nosed girls

at Parkfield Cedars…..

Comments on

other contributions

Email: October 2nd, 2005

What a pleasure it was to

read

John Garratt's piece on school dinners.

A delightful piece of atmospheric writing. John and I were colleagues many

years ago on the Evening Telegraph. How strange therefore I didn't realise

he and I had both been at the Central School -- or perhaps I did and had

forgotten.

I stopped having school dinners after consuming a

cheese pie that made me violently sick. As a result I didn't eat cheese for

many years afterwards. I did resume school dinners after a while. I think my

mother got fed up of giving me "packing up" especially when food became

harder and harder to get.

I also read

Peter Eyre's piece with interest. He

and I must have worked together on the Telegraph which I joined in 1946 but

I cannot for the life of me place him. As he rightly says memory plays

strange tricks. He is right of course about there being a school special

trolley bus from the Market Place to Darley Park. Because it looked like any

other Corporation bus it became fixed in my mind as a service bus. In fact I

think we often had to catch a service bus especially if we had been waiting

in the cold and rain during winter to catch the bus from Alvaston into town

after the special had gone. Now I come to think about it there was also a

special school bus from the Darley Park terminus down the Broadway

to...where? Can't remember!

Two other points from

Peter's email: I never meant to suggest the 1940 intake list was complete

because I'm sure it wasn't. And re. Don Acford: sorry if I spelled his name

wrongly but I was never sure if it was Ackforth or Ackford. One further

point: I certainly never meant to suggest that no one bothered about the

war. Very much the contrary: it was with us all the time. The point I was

making was that as far as I was concerned (and my experience was obviously

different from Peter’s) the teaching staff rarely mentioned it and certainly

didn’t bring it (as they could easily have done) into any of our lessons,

especially French and Geography as well as History.

Peter’s article also reminds

me that the “tarty teacher” I mentioned in one of my articles must have been

the Miss Ferguson he refers to. And that reminds me of another woman teacher

who was only with us for perhaps a year if that -- Miss Collis. She was a

very pleasant easy going lady, quite young, who had the misfortune to have a

rather unsightly wart on her face.

More later but meanwhile all the best. Patrick (Morley)

Other of Patrick's

memories were published in the DET Bygones section [Home] Page updated:

Saturday, 04 August 2007 |